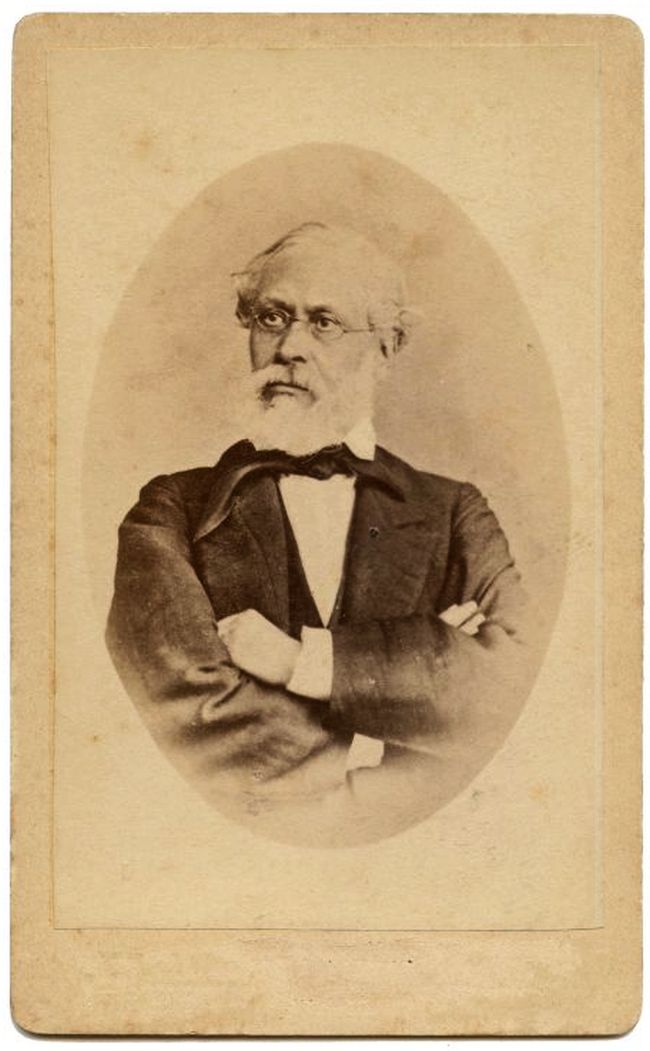

Cezar Bolliac

Cezar or Cesar Bolliac, also known as Boliac, Boliacu, Boliak and Boleac (transitional Cyrillic: ЧeсарȢ БoliaкȢ; 23 or 25 March 1813 – 25 February 1881), was a Wallachian and Romanian writer, scholar, and political figure. Born to non-Romanian parents, he joined the local aristocracy, or boyardom, by adoption into the Pereț family. He was briefly a cadet in the Wallachian military forces, but resented the Russian Empire, which had brought Wallachia into its sphere of influence; he took up writing and publishing, and for a while edited a literary magazine called ''Curiosul''—bridging neoclassicism and romanticism. Like other Romanian liberals and Freemasons, Bolliac fought the Russian constitutional arrangement, or ''Regulamentul Organic'', seeing it as a remnant of feudalism. He was therefore caught up in the anti-Russian conspiracy of 1840, and was detained on orders from Prince Alexandru II Ghica. He was ultimately released through the intervention of other Ghica family members, who remained his friends and protectors.

Cezar or Cesar Bolliac, also known as Boliac, Boliacu, Boliak and Boleac (transitional Cyrillic: ЧeсарȢ БoliaкȢ; 23 or 25 March 1813 – 25 February 1881), was a Wallachian and Romanian writer, scholar, and political figure. Born to non-Romanian parents, he joined the local aristocracy, or boyardom, by adoption into the Pereț family. He was briefly a cadet in the Wallachian military forces, but resented the Russian Empire, which had brought Wallachia into its sphere of influence; he took up writing and publishing, and for a while edited a literary magazine called ''Curiosul''—bridging neoclassicism and romanticism. Like other Romanian liberals and Freemasons, Bolliac fought the Russian constitutional arrangement, or ''Regulamentul Organic'', seeing it as a remnant of feudalism. He was therefore caught up in the anti-Russian conspiracy of 1840, and was detained on orders from Prince Alexandru II Ghica. He was ultimately released through the intervention of other Ghica family members, who remained his friends and protectors. Upon his return, Bolliac continued to test censorship, inventing a style of social poetry that favored the exploited peasantry, and expressing sympathy for the Romani underclass, which had been enslaved by the boyars. He discarded liberalism for utopian socialism, and then, briefly, for a variant of communism; he combined such views with Romanian nationalism, moving it from romantic to left-wing variants. Reaching out to fellow Romanian nationalists in Moldavia and throughout the Austrian Empire, he became involved with researching the origin of the Romanians, performing his first archeological digs along the Danube and in the Southern Carpathians; the landscape provided him with inspiration for romantic elegies, which endure as some of his best works as a poet. Bolliac was an increasingly sarcastic critic of Westernization, earning praise for his journalistic wit, and a rediscoverer of Romanian folklore. He became convinced that the Romanians were primarily descendants of the Dacians—a romantic and post-romantic ideology that was later taken up by Bogdan Petriceicu Hasdeu, and mutated into Dacianism.

Under Prince Gheorghe Bibescu, who embraced nationalism, Bolliac was a poet laureate and a public prosecutor. This did not prevent him from participating in the liberal conspiracy that ultimately became the Wallachian revolution of 1848. He entered the provisional government that toppled Bibescu, also serving the cause as a journalist and propagandist. Involved on the abolitionist side of revolutionary politics, he allegedly embezzled the financial contributions that slaves owed upon their release. In late 1848, the Ottoman Empire restated its control of Wallachia, arresting the rebels—Bolliac was deported with various of his colleagues to Orschowa, whence they either escaped or were allowed to leave. He sought refuge among the Romanians of Austrian Transylvania; deep into 1849, he supported forming a revolutionary alliance with the breakaway Hungarian State, and, alongside his colleague Nicolae Bălcescu, approved of the Hungarian–Romanian pacification act. He fled the Russian invasion, reaching Istanbul; once there, he came to be distrusted by both the Romanian and Hungarian exiles—viewed as a fanatic by the former, and alleged by the latter to have stolen diamonds obtained from the Zichy family.

Evading prosecution by the Ottomans and the Austrians, Bolliac spent the years 1850–1857 in Paris; here, he was won over by the cause of Moldo–Wallachian unionism, as a preliminary step to establishing a Greater Romanian, or "Dacian", state. He popularized this cause to an international audience during the Crimean War, returning to Wallachia just as the war had ended. He was involved in creating the United Principalities (in 1859), suggesting that Moldavia's Alexandru Ioan Cuza be selected as ''Domnitor''. Bolliac also endorsed the more radical points on Cuza's agenda, including land reform, and, as head of the National Archives, collected documents allowing for the secularization of monastery estates. He opposed both Cuza's other political stances (to the point of being imprisoned for ''lèse-majesté'') and the "monstrous coalition" that had been formed against the ''Domnitor''. He spent most of the 1860s involved in political quarrels, often carried through his newspaper, ''Trompeta Carpaților''. Discarding socialism for economic nationalism, Bolliac also embraced violent antisemitism; he initially also opposed the foreign-born ruler, Carol of Hohenzollern, but later found a role for the monarchy in his political vision, copying Bonapartism. Though he made important discoveries at Zimnicea and elsewhere, he came to be widely ridiculed for his drift into pseudoarchaeology, and also shamed, though never prosecuted, as an alleged child sexual abuser. He died after a losing battle with paralysis, leaving a tarnished legacy—though regarded as a hero by the communist regime, especially in the 1950s, it was through his supposed compatibility with Marxism. Provided by Wikipedia